Title: Where are the engineers?

Usman begins his presentation by showing us two pictures—one of the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, and one of a “fake lake” from the site (a “flake”!), built so that tourists can enjoy an air conditioned, accessible “countryside” without actually having to go into the country (man, what would Ed Abbey say about that?). Tons of money was quite obviously spent on setting up the infrastructure for the Olympics, but what was much less visible was the destruction of public lands, the displacement of homeless and indigenous peoples, and the disproportionate impacts on people of color and living in poverty—all created by the investment in the infrastructure itself.

So, the question we have to ask about this contradiction is, Where are the engineers? What do engineers interested in justice have to say about this?

Answers might come to us from authors like Audre Lorde, whose famous essay on “dismantling the master’s house” argues that we cannot take down the “master’s house”–dominant structures of control or power—with the master’s tools. Other tools of deconstruction (and even destruction) are required. Here are some good tools:

Ursula Franklin provides us with some tools for doing this dismantling work. Usman notes that one of Franklin’s arguments was that “prescriptive production leads to injustice” and is “not challenging assumptions of systems” that are unjust. For example, one justification for the invention of sewing machines was to make “women’s work” easier. At the same time, however, sewing machines led to the means of exploiting vast numbers of women in unjust industrial work (i.e., in sweat shops).

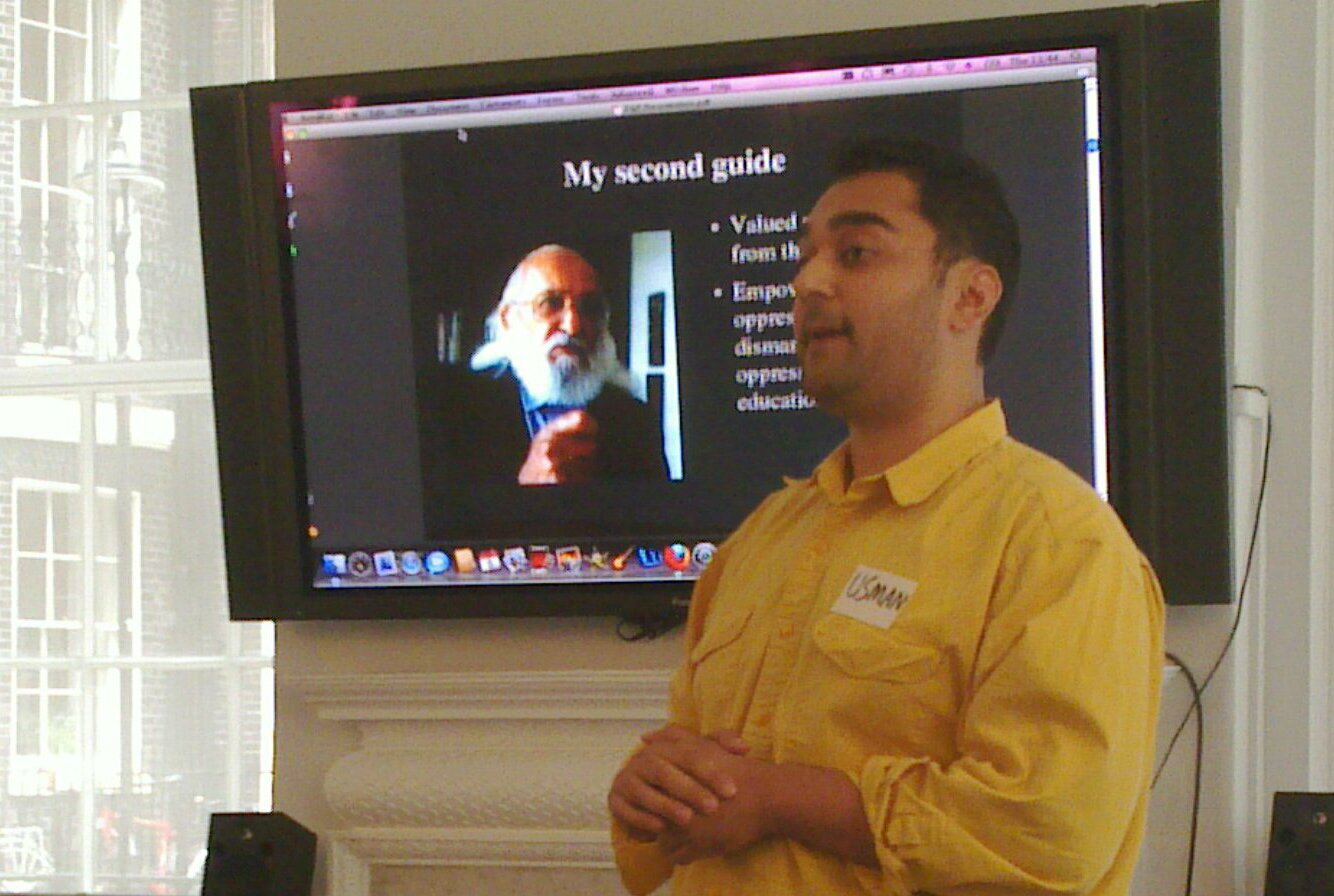

More inspiration comes from Paulo Freire, whose work Pedagogy of the Oppressed suggests some of the ways in which the master’s tools (such as language, or formal education) are unjust and imprisoning. He proposes ways we might subvert and dismantle these structures of injustice. He believed “resistance was necessary to breaking oppression,” and that people need to go through a process of “conscientization” so as to come into consciousness of their own role as the oppressed, but also as having the agency to resist that oppression.

In Engineering and Social Justice, Donna Riley argues that claiming our own autonomy might be a crucial first step in promoting or claiming social justice. Usman notes that one interesting historical example of this would be artisan guilds in the Netherlands. The guilds functioned as collective entities, protecting the autonomy of its members. Reciprocity is a key part of this, too—artisans need to be able to provide feedback about whether and how things are to be built, rather than just “doing what they are told.”

So what does this mean for engineering? Usman wraps up by arguing that it is not so much a need to set up steps, loops, graphs or flowcharts, but of adopting a mindset geared to dismantling the master’s house.

Jen wonders: Usman notes that these are “tools” for dismantling the master’s house, yet these tools look very different from those that many engineers are used to using. It strikes me that a presentation like Usman’s is aiming at a “conscientization” of its own—to begin to signal to engineers or sensitize them to different ways of seeing and being in the world. But, in practical terms, I wonder if some engineers might wonder or ask, “Okay, so I’m starting to get it. I’m interested in this justice stuff. So now what?” Are there structures or support networks that are reaching practicing engineers or engineering students who do enter this justice-oriented consciousness, or who are already there?

In other words, what responsibility do we have to students to not only expose them to various forms of consciousness or awareness, but also to provide them with real tools for resistance. Say you are an engineer working in a cube at a firm that gets primarily defense contracts. What kind of a “guild” might serve this engineer? To do what? Is autonomy even possible in this context, or are we only interested in reaching engineers already outside these corporate settings?

I’m thinking of Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, a book about different modes of social resistance that calls us to be aware of power differentials. He argues there is a difference between “strategies” and “tactics.” We can have “strategies” to fight for social justice—plans to fight against structures of inequality. To enact these strategies, however, frequently requires a priori a certain amount of status or power to begin with. What about people who are embedded (trapped?) in systems in which power or autonomy are not easily acquired or accessed?

De Certeau argues that in this case, we need to pay attention to “tactics,” the ways in which the disenfranchised or disempowered subvert structures of power or oppression by turning the system back on itself. Workers in a factory setting, for example, may do their work more slowly so as to subvert productivity quotas. Or they might purposely break machinery in order to secure breaks themselves. De Certeau reminds us that these subversive acts have revolutionary value—though not as visible—just as strategies do. These arguments, and ones like them (such as those made by Scott in Seeing Like a State) deserve our attention as we label which forms of consciousness are “really” just and deserve our attention and encouragement.